SEND Hub

Supporting Pupils with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) at St Monica’s Catholic Primary School

At St Monica’s, we are committed to being inclusive and welcoming to all pupils. Every child is valued, and we strive to ensure that all children, regardless of their abilities or needs, can thrive academically, socially, and emotionally.

Our school has a range of support available for pupils who may need extra help. This includes classroom-based strategies, pastoral care, and access to specialist services. We work closely with external professionals such as the Sefton ASD Team, Occupational Therapists, School Nurses, Inclusion Consultants, and Speech and Language Therapists to ensure that every child receives the right support.

We also recognise the importance of mental health and wellbeing. Pupils have access to counselling, play therapy, and the Mental Health Support Team. Our Pastoral Lead, Mrs Hough, provides additional care and guidance to help children feel happy, safe, and supported in school.

Parents are central to everything we do. We encourage open communication and involve parents fully in any discussions or plans regarding their child. You can share any concerns by contacting your child's class teacher or a member of the SEND Team at finance.stmonicas@schools.sefton.gov.uk or on 0151 525 1245.

At St Monica’s, we believe that every child can succeed in a mainstream setting wherever possible. We work closely with families and the Local Authority to make sure that pupils with SEND are fully included in school life and have the best possible opportunities to reach their potential.

For more information about local SEND services and support, please visit Sefton Council’s Local Offer, which provides guidance for children and young people aged 0–25 with SEND.

To outline the details of our SEN provision, we have created the following information report and policy:

Please contact a member of the St Monica's SEND Team if you have any concerns:

Mrs Fate (SENDCo/Senior Mental Health Lead)

Miss Byrne (EYFS/KS1 Assistant SENDCo)

Miss McGiveron (KS2 Assistant SENDCo)

Mrs Hough (Pastoral Lead)

ADDvanced Solutions - Spring 2026

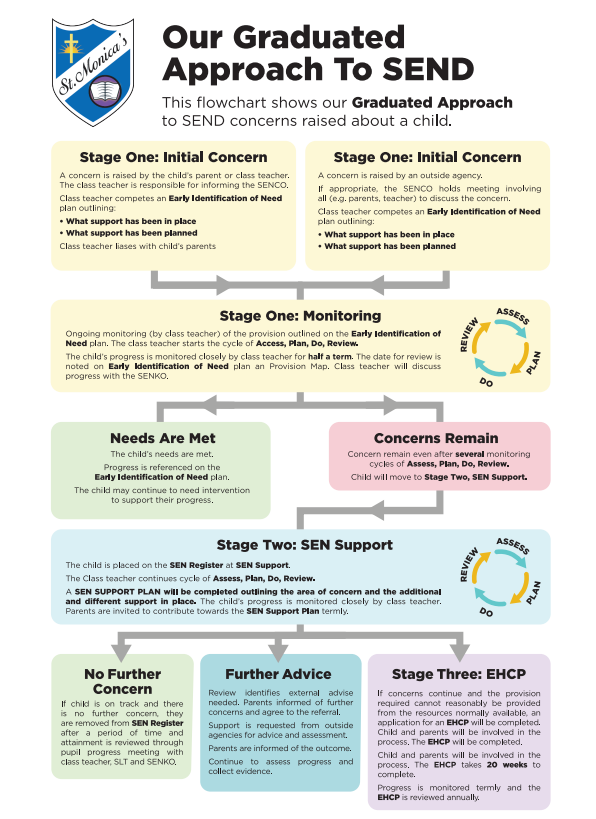

St Monica's Graduated Approach

ADHD

ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) is a neurodevelopmental condition. It can also be known as ADD (attention deficit disorder). The symptoms can be split into 3 categories, difficulties with attention, hyperactivity and impulsivity.

ADHD is a form of neurodiversity. This means that children and young people with ADHD think and work differently as their brains work slightly differently. ADHD does not affect intelligence. It cannot be 'cured' and it cannot be 'outgrown'. Children and young people with ADHD will grow up into adults with ADHD.

Types of ADHD

There are 3 types of ADHD.

Inattentive - This can look like your child being easily distracted, forgetful, having difficulties focusing on tasks or spacing out.

Hyperactive or impulsive - This can look like being fidgety, very energetic, impulsive, overly talkative or having racing thoughts.

Combined - This is the most common type of ADHD. It's a combination of the inattentive and hyperactive types.

ADHD traits

ADHD has a wide range of characteristics and traits. There isn't a specific way that ADHD 'should' look. ADHD can look very different in each child. Every child is unique, so their ADHD traits are going to be unique too.

The ADHD traits can be spotted at an early age. It's not usually possible to diagnose children with ADHD until they are 6 years old. This is because the traits associated with ADHD are part of the typical development of children between 2 to 5 years old. For example, we expect children under 5 to find it hard to sit still for long periods of time. ADHD traits often become more noticeable when children start school.

There are differences in how boys and girls show their ADHD traits. For example, boys are more likely to show their hyperactivity by running around or being disruptive. In girls, hyperactivity can look like talking a lot, doodling or fidgeting in their chair.

Impulsive

- Finds it hard to wait for their turn

- Interrupting people when they speak

- Answers before a question is completed

- Acts without thinking like jumping off playground equipment without thinking how or where they'll land

- Expresses frustration by punching or screaming

Inattentive

- Careless or silly mistakes in school work or activities

- Short attention span

- Does not appear to be listening

- Struggles with organising

- Avoids tasks that require lots of attention for a long time

- Easily distracted

- Loses things like toys, clothes, keys or homework

- Forgetful

- Does not notice when they need to eat, drink, sleep or go to the toilet

Hyperactivity

- Fidgets a lot

- Struggles to stay in their seat

- Moves around a lot- like being powered by a motor

- Loud

- Doodles a lot

- Talks a lot

- Focuses on a specific topic or activity without noticing

-

ADHD strengths and 'superpowers'

It can be easy to focus on what your child or young person is struggling with. People with ADHD have lots of different strengths that they can offer. It's really important to highlight your child or young person's strengths to them.

People with ADHD can be:

- adaptable

- creative

- curious

- energetic

- enthusiastic

- empathetic

- flexible

- funny

- good under pressure

- good at lots of different skills (a jack of all trades)

- good at making connections

- good at seeing and understanding emotions (emotionally intelligent)

- good at spotting patterns

- good at understanding things instinctively (intuitive)

- open to new experiences

- original

- passionate

- persistent

- quick learning

- resourceful

- resilient

- spontaneous

-

These are only some of the strengths your child or young person may have. Your child or young person's strengths will be as unique as they are.

-

Helping your child or young person with ADHD

It can be difficult to know where to start to help your child or young person with their ADHD. ADHD cannot be 'cured', but you can help your child or young person to manage their symptoms.

ADHD cannot be managed just using medication. Managing ADHD symptoms needs a combination of different elements, including:

- learning and understanding ADHD (also known as psychoeducation)

- a whole person approach

- medication

- therapy

- behavioural strategies

-

Routine, structure and being consistent

Adding fixed routine and structure to your daily family life is really important. Routine, structure and staying consistent can really help children and young people with ADHD manage their behaviour.

Children and young people with ADHD can struggle with 'in-between' times. These are the times when they don't have complete freedom like on a playground but they also don't have clear structure like in a classroom.

Clear communication

Being able to communicate clearly is helpful for all children and young people. It can be particularly helpful for children and young people with ADHD.

The following techniques can help you to communicate clearly with your child or young person:

-

Make sure you have their attention before speaking. You can do this by calling your child by their name before you speak and waiting for them to look.

Try to be face-to-face with your child or young person. Get down to their level. You can do this by lying down or crouching. It makes it easier for them to see what you're saying. It also shows your child or young person that you're interested and helps them listen to you.

Speak clearly and enthusiastically. Use simple and direct words. Being enthusiastic shows you are interested in what they are saying and will help them to listen to you.

When giving instructions, give them clear step-by-step instructions. It may also be helpful for your child or young person to write down instructions so they can remember the steps.

Do not give them a new instruction whilst they are mid-task. Children and young people with ADHD can struggle to remember instructions. This will be even harder if they are already in the middle of a task or activity.

Sensory Processing

What is Sensory Processing?

Sensory processing is the process of taking in information from the world around us, making sense of that information and using it to act and respond in an appropriate manner. Information about our own body and the world is gathered from the 7 senses.

- Touch (Tactile)

- Movement (Vestibular)

- Body position (Proprioception)

- Sight (Vision)

- Sound (Auditory)

- Smell (Olfactory)

- Taste (Gustatory)

What are the signs of sensory processing difficulties?

Everyone has some sensory processing difficulties now and then, because no one is well regulated all the time. However for some individuals sensory processing difficulties can have a significant impact on their daily life. For example:

- Overly responsive to touch, sights or sounds

- Under responsive to movement, sights or touch

- Difficulties in organising and carrying out everyday activities

Sensory Service Pathway

Sefton Community Occupational Therapy Service offers parent / carer sensory workshops to equip parents with knowledge and skills to reduce the effect that sensory processing difficulties have on their child’s daily life.

The workshop lasts approximately 2½ hours and will include a presentation on ‘Understanding Sensory Processing’ followed by a question and answer opportunity.

A workbook full of strategies and ideas to help will be provided during the workshop.

The Community Occupational Therapy Service is an advice and strategies only service, we do not work directly with your child.

There will be opportunities for further advice and support following attendance at a workshop.

Sensory workshops can be accessed through completion of a referral form by parent / carer. Referral forms can be requested by contacting your local Occupational Therapy Team – details can be found on the back of this leaflet.

Please Note: The workshop is for adults only and unfortunately children cannot be accommodated. You may be offered a virtual or pre-recorded webinar rather than a face to face workshop.

How to Contact Us

Email us on seftoncommunity.physio-ot@nhs.net

South Sefton

Sefton Carers Centre, 2nd Floor, 27-37 South Road, Waterloo, L22 5PE

Dyslexia

What is Dyslexia?

Dyslexia is a common learning difficulty that mainly causes problems with reading, writing and spelling. It's a specific learning difficulty, which means it causes problems with certain abilities used for learning, such as reading and writing.

The British Dyslexia Association (BDA website) has adopted the Rose (2009) definition of dyslexia:

"Dyslexia is a learning difficulty that primarily affects the skills involved in accurate and fluent word reading and spelling. Characteristic features of dyslexia are difficulties in phonological awareness, verbal memory and verbal processing speed. Dyslexia occurs across the range of intellectual abilities. It is best thought of as a continuum, not a distinct category, and there are no clear cut-off points."

Dyslexia is a specific learning difficulty which primarily affects reading and writing skills. However, it does not only affect these skills. Dyslexia is actually about information processing. Dyslexic people may have difficulty processing and remembering information they see and hear, which can affect learning and the acquisition of literacy skills. Dyslexia can also impact on other areas such as organisational skills.

It is important to remember that there are positives to thinking differently. Many dyslexic people show strengths in areas such as reasoning and in visual and creative fields.

Delphi definition of dyslexia

Dyslexia is a set of processing difficulties that affect the acquisition of reading and spelling.

In dyslexia, some or all aspects of literacy attainment are weak in relation to age, standard teaching and instruction, and level of other attainments.

Across all languages, difficulties in reading fluency and spelling are key markers of dyslexia.

Dyslexic difficulties exist on a continuum and can be experienced to various degrees of severity.

The nature and developmental trajectory of dyslexia depends on multiple genetic and environmental influences.

Dyslexia can affect the acquisition of other skills, such as mathematics, reading comprehension or learning another language.

The most commonly observed cognitive impairment in dyslexia is a difficulty in phonological processing (i.e., in phonological awareness, phonological processing speed or phonological memory). However, phonological difficulties do not fully explain the variability that is observed.

Working memory, processing speed and orthographic skills can contribute to the impact of dyslexia.

How can you help your child?

Spelling

Spelling is one of the biggest, and most widely experienced difficulties for the dyslexic child and adult. Most dyslexic people can learn to read well with the right support, however, spelling appears to be a difficulty that persists throughout life.

It's not entirely understood why this is the case. It is known that dyslexia impacts phonological processing and memory. This means that dyslexic individuals can have difficulty hearing the different small sounds in words (phonemes) and can't break words into smaller parts in order to spell them.

Many children with dyslexia find it difficult to learn how letters and sounds correspond to each other and may not be able to recall the right letters to be able to spell the sounds in words. The complexity of the English language means that learners also have to remember irregular spelling patterns and sight words such as the, said, was.

Although spelling is likely to be something that a dyslexic person always finds challenging, there are strategies that parents and teachers can put in place to support learning.

- Help your child to understand words are made up of syllables and each syllable has a vowel sound. Say a word and ask how many syllables there are. Help your child to spell each syllable at a time

- Write words in different coloured pens to make a rainbow or in shaving foam, flour or sand over and over again to help your child remember them

- Look with your child at the bits in the words which they find difficult - use colours to highlight just the tricky bit

- Look for the prefixes and suffixes in words, e.g. -tion, -ness and learn these chunks. Explore with your child how many words have the same chunks at the beginning or the end of words

- Use flashcards or play matching games to let your child see the words lots of times - the more times they see the word, the better they will be able to read and spell it

- Use cut out or magnetic letters to build words together, then mix up the letters and rebuild the word together

- Use mnemonics - silly sentences where the first letter of each word makes up the word to be spelled

- Find smaller words in the bigger word, for example 'there is a hen in when'

- Go over the rules of spelling together, e.g. a 'q' is always followed by a 'u'. Ask your child's teacher for the rules they teach in class

Homework

Homework can be a frustrating and upsetting experience for dyslexic students and their parents.

For a student with dyslexia it's not just the homework task itself that can be challenging, many dyslexic people can really struggle with organisation, concentration and short term memory. All of these things can make homework a daily source of confusion and frustration. This can result in a reluctance to try and poor self-confidence.

There are strategies that every parent can put in place to support their child's learning.

Establish a routine

Dyslexic learners may find it difficult to maintain concentration for long periods of time and may get tired quickly, so it's a good idea to create a routine which emphasises 'a little and often' rather than trying to squeeze too much work into a longer session.

Remember to take after-school activities into account when you develop your homework plan.

Encourage your child to write down what is needed for the next day and to check the list before they leave for school/college.

Support your child

Be encouraging. Praise your child when they are trying their best, and focus your praise 'It was really good when you..'.

Go over homework instructions together to make sure they understand what they are supposed to do. You can help your child to prepare for tasks and generate ideas together before they start work.

If your child has difficulty writing homework down at school or remembering tasks, talk to their teacher so that the homework is given to them on a worksheet or can be accessed via the school's website.

Checking work

Help your child learn to check their own work, so this becomes a natural part of the homework routine as they get older. Your child may find working on a computer easier than writing. Show them how to use the spellcheck facility and help them learn to touch type.

Other useful strategies include:

- Reading work out loud or using text-to-speech software to read work back – this can help to identify errors that your child might miss when they read silently

- Making a list of frequent spelling, punctuation, and grammar mistakes to check against. For example, if your child often misses capital letters, make sure that's on the list.

Organisation

Dyslexic people can really struggle with organisation. For an older child technology such as a mobile phone will be a helpful tool. They can take photos of any important information, set reminders of important events or deadlines and record voice messages as a reminder.

Other useful strategies are to:

- Help your child to make a written homework plan which includes tasks and deadlines, and revision plans.

- Colour-code subjects and make sure all notes for a particular subject are kept together in folders.

- Create visual reminders such as a prominent calendar or 'to do' list.

Study skills

Try to help your child build successful study skills for example, by creating a revision timetable, by using different techniques for revising and reviewing learning, e.g. using mindmaps, by talking through or recording what they've learned, or by thinking of different ways to complete a particular task.

Encourage them to think of coping strategies for when they get 'stuck'. For example, who would be the right person to ask for help if they are unable to tackle a problem on their own.

Dyscalculia

What is Dyscalculia?

Dyscalculia is a specific and persistent difficulty in understanding numbers which can lead to a diverse range of difficulties with mathematics. It will be unexpected in relation to age, level of education and experience and occurs across all ages and abilities.

What is Dyscalculia?

The term Dyscalculia is often used to describe someone who unexpectedly struggles to understand and achieve in Maths. The important points to note are as follows:

- A specific learning difficulty in Maths is more common than dyscalculia.

- A specific learning difficulty in Maths is caused by processing difficulties that impact on mathematical skills.

- Dyscalculia is a difficulty particularly in understanding and working with numbers.

- With dyscalculia, we may see age related difficulties with naming, ordering and comparing physical quantities and numbers, estimating and place value.

- The impact of such difficulties on an individual’s mathematical ability can vary across individuals and across the lifespan.

- Any difficulties in Maths may be affected by other factors including the environment and any co-occurring difficulties.

-

How is dyscalculia different from other maths learning difficulties?

The word dyscalculia is often used to describe someone who finds maths unexpectedly hard. But in reality, there are many different reasons why someone might struggle with maths—not all of them are due to dyscalculia or a specific learning difficulty (SpLD).

People may have a Specific Learning Difficulty (SpLD) in maths when:

- Their difficulties are shown to be caused by cognitive factors such as language and reasoning skills, working memory, spatial skills or executive functions and

- Result in low attainment in some/all areas of maths and

- Have a significant and sustained impact on their learning, work and daily activities.

-

Difficulties experienced by some with a SpLD in maths may include:

- Difficulties with counting, especially backwards

- Using counting forwards in ones to add and backwards in ones to subtract beyond their peers

- Difficulties remembering and using number bonds and multiplication facts

- Not able to use number relationships to make calculations easier – e.g. add 9, rather than add 10 subtract 1; counts up in 6s for 5x6 rather than using knowledge of 6, fives.

- Using written methods for all calculations (34+11; 29 – 2; 30x2; 10/5)

- Using procedures without understanding them

- Not knowing when to use multiplication or division

- Difficulties in solving word problems – unable to visualise the maths needed

- Difficulties in understanding algebra and formulas

- Having to count and re-count, even small quantities, excessively

- Difficulties with estimating quantities, measurements, time and money

- Not understanding when/why an answer is unreasonably large or small

- Not understanding that £14.99 is less than £20;

- Not noticing when a price/ restaurant bill is incorrect and unreasonable

- Difficulties in judging time (arriving late or very early), understanding timetables and planning travel.

- A much fewer number of people will have such a pronounced difficulty with understanding quantities and numbers, that they will meet the criteria for having dyscalculia.

- Examples of the difficulties that people with dyscalculia may have include:

- Having to count and re-count, even small quantities, excessively

- Difficulties with estimating quantities, measurements, time and money

- Not understanding when/why an answer is unreasonably large or small

- Not understanding that £14.99 is less than £20;

- Not noticing when a price/ restaurant bill is incorrect and unreasonable

- Difficulties in judging time (arriving late or very early), understanding timetables and planning travel.

Autism Spectrum Condition

What is Autism?

Autism is a lifelong neurodevelopmental condition that can be recognised from early childhood. Each autistic person will have their own individual strengths and challenges.

Autistic people will have some challenges around social interaction and communication. For some, there may be limited or no spoken communication but often the challenges can present difficulties in understanding others’ intentions, social cues, body language and/or facial expressions. Social interactions can be hard work for autistic people.

There is usually a “preference for sameness” and a tendency for restricted or repetitive patterns of thought or behaviour, this can present in several different ways. Repetition and familiarity can be comforting and help to manage anxiety. Unexpected changes or breaks from familiar routine can be difficult and an autistic person might need longer to process these.

Autistic people often have sensory differences and can experience sound, smells, sight, taste and touch so acutely that this can be really overwhelming at times.

For more information about ASC, follow the link to ADDvancedSolutions website here: https://www.addvancedsolutions.co.uk/neurodevelopmental-conditions/autism/